This week we asked you all on twitter and instagram which kinds of beers you wanted to learn about our design process for. The twitter crowd were heavily skewed towards Heritage Ales rather than Contemporary Beers, but the majority wanted a bit of both. On Instagram, we could only give two options (Heritage and Contemporary) and the opposite result came through – that group wanted to know about how we design our Contemporary Beers. As a result of this very unscientific experiment, we’re going with “a bit of both”, but it seems Beerblefish founder, James Atherton, has quite a lot to say on the matter, so we’re splitting this into two parts – a blog mini-series, if you will.

We’ll be writing about how we design beers in this weekend’s blog. What should we focus on?

— Beerblefish Brewing (@beerblefish) August 20, 2020

First up, some general stuff about beer design at Beerblefish, and then we’ll dive into the Heritage Ales bit.

Beer design Beerblefish-style

Everyone working at Beerblefish has the chance to design beers – we’ve all got our own tastes and preferences, which means we can produce a wide variety of products and create something for everyone. However, there’s one overriding principle – we don’t make beers that we don’t like!

We also believe that beer should be beer. While we do sometimes add things beyond the basic ingredients that make beer, we would never want to turn it into something that tastes like it isn’t beer. We could get into all sorts of philosophical tangles here about whether something “tastes like beer” if enough people make it and call it beer, but we think you’ll know what we mean if we just say beer should be beer.

All our beers are vegan. This means we don’t add isinglass to our beers, but it also means that we won’t add animal-derived ingredients as flavourings, too. You won’t find honey or lactose in any of our products, for example.

Right, let’s get down to the nitty gritty. How do we actually go about deciding what a beer should be like?

The first thing we do is decide what the beer is for. Drinking, obviously, but in what context? Is it for a long session at the pub or in front of the TV? Is it going to take centre stage at your next dinner party? Or is it perhaps something to savour a small glass of when you only want one?

Then we think about when we’re going to brew it and drink it – as in the time of year, not the time of day. Generally, we (and, it seems, the general public) drink more of the heavier, darker ales in winter and more of the lighter, paler beers in summer, but there are exceptions to this. Mild, for example, is a fantastic drink for a warm day because of its relatively thin body and low bitterness, which is one of the reasons we make our annual mild in May.

However, one of brewing’s little ironies is that brewing a lager in high summer is virtually impossible without very significant chilling capacity and if you brew a stout in winter, you risk the yeast going to sleep unless you have heating. We’re still really tiny and these facilities that larger breweries might consider basic are currently unattainable luxuries for us.

Designing Heritage Ales

Our Heritage range currently comprises three beers inspired by the nineteenth century. I asked James how he would go about adding a sessionable ale to this range. He said that he would start by looking at the research he’s gathered over the years, including books, research papers, archival records from breweries and online resources such as the fantastic “Shut Up About Barclay Perkins” blog run by historical beer author Ron Pattinson.

James looks at the research to find out what types of ingredients were used and the proportions they were used in, taking account of the way that malts, hops and yeasts have changed in the intervening period. “If I were to use UK extra pale malt for a heritage ale, it would be too pale – nineteenth century pale ales were much darker than we would expect a modern pale to be.”

The first decision point is whether the beer will be dark or pale, which then determines what the malt bill will look like. “Nine times out of ten, I’d choose Maris Otter as a base malt. I’d love to use heritage malts for the base, but the cost is prohibitively expensive at the moment.” James would usually add a crystal malt for colour and body, and if he’s aiming for a darker beer, he’ll consider adding roasted malts or wheat. He tends not to use inverted sugar – even though it would be authentic to the period, it’s difficult to work with and get the right results from when using the quantities required.

The mash and sparge process usually lasts 90 minutes to two hours – not as long as a nineteenth century brewer would have taken, but longer than a modern beer would require. Beerblefish uses a single infusion sparge from the top – some Victorian breweries would have used European-style decoction mashes or underlet sparges, but these methods would be very difficult (perhaps impossible) on our kit.

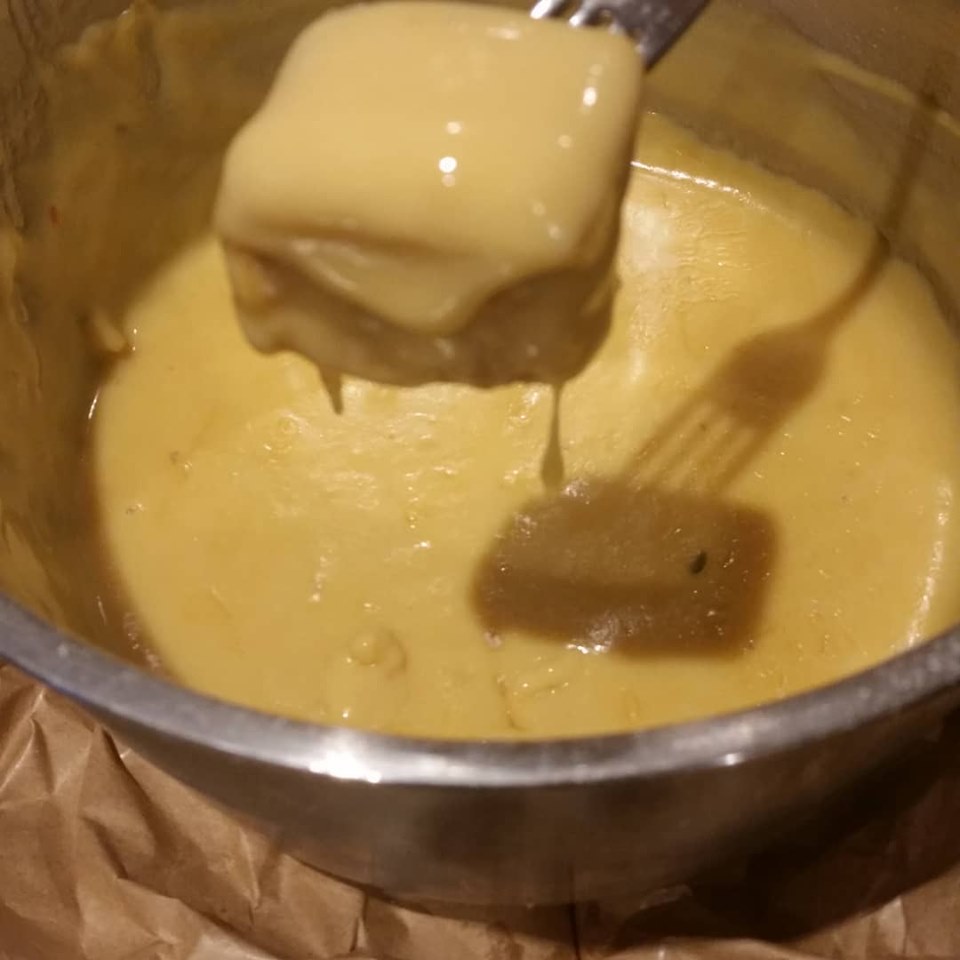

The second we’re over the element when transferring from the mash tun to the kettle, we put the elements on. Directly-fired coppers were common in the 1800s, so the early wort would have got a hint of caramelisation – putting our electric elements on very early allows us to replicate this, and it contributes to the rich body of our Heritage Ales, especially our 1892 IPA.

James also adds at least a handful of hops to help stop foaming. He says, “Without modern anti-foam, I think it’s likely that a sensible Victorian brewer would have done this to prevent foaming. They paid duty on the malt used, not the alcohol content like today, so sparge and boil efficiency were key and brewers wouldn’t have wanted to waste vessel space with foam.”

We always try to use whole-leaf hops for our heritage ales. Our bittering hops always contain a Goldings or Fuggles variety. Our Heritage Ales are not a copy of an 1800s recipe – they are always given a slight modern twist. We often use, for example, Weyermann’s CaraAroma malt in a very small percentage because James likes the slight honey flavour it gives without actually having to add honey to the brew.

The hops used at flame-out will often be modern; just as the brewers in the 1800s used the then-newfangled Fuggles hops, we might add some new US, Australian or New Zealand hops to give the beer our own modern twist.

The boil for a Heritage brew will be at least 60 minutes and we don’t worry if it goes up to 90 minutes. We don’t do the two or three hour boils that the Victorians might have used because we have to get a brew done in a day and our staff aren’t working 16-hour shifts!

We don’t have a coolship, a common piece of kit in the nineteenth century, so we have to chill through a plate chiller. We’d love a coolship. One day.

Our fermenting vessels are stainless steel, not wooden. To help simulate nineteenth century wooden vessels, we pitch into primary fermentation a small amount of Brettanomyces claussenii, which is a British strain of brettanomyces. This helps replicate that even with steam sanitation in the 1800s, brewers would have been unlikely to have purged all the brettanomyces from the wooden vessels. James says, “Pitches tended to be mixed fermentation – multiple yeast and bacterial strains. Many British brewers would have used something like the Burton Union system or would have top cropped and pitched yeast into fresh wort. This means you would have an ever-evolving mixture of yeasts and bacteria.”

At Beerblefish, we use dried and wet yeasts. James will typically design a Heritage Ale with between one and three different saccharomyces strains and Brettanomyces claussenii. We tend to pitch warm (up to 25 degrees Celsius) and then chill the fermenting wort. This method is beneficial to the brettanomyces, which likes to be warm, and it can also add fruity esters from the British ale yeasts that we use. We once pitched British ale yeast in a test batch at 32 degrees Celsius and held it there for two days, which led to a delicious banana flavoured beer!

We’ll normally allow fermentation to run for 10 to 14 days. Fermentation needs to be warm to allow brettanomyces to do its magic. British brettanomyces doesn’t attenuate as completely as some of its Belgian counterparts, so there is a fruity sweetness left in the beer that you wouldn’t get with, for example, a typical gueuze.

James says, “All this may sound like how you make beer, but each of these stages in the process of making beer contributes different flavours to the final beer and the whole process must be considered, not just what’s in the malt, hop and yeast bills.” James reckons that with the same malt, hops and yeast, he could make you many different beers depending on how long you mash for, how long you sparge for, the boil time, the style of elements in the kettle, the times at which the hops are added, the temperature yeast is added at, the temperature of the primary fermentation, whether you give the beer a diacetyl rest…there is an enormous list of variables that contribute to the art and science of designing a Heritage Ale.

Come back next week to find out how we design the beers in our Contemporary range.

Recent Comments